You are here

Magnoliopsida

Cinchona L.

EOL Text

The genus Cinchona includes at least 23 species of trees and shrubs that are native to the Andes of South America and the mountains of southern Central America. The trees have showy white, pink, or purple flowers that are generally pollinated by butterflies and hummingbirds, and dry capsular fruits with flat, papery seeds that disperse on the wind. Most of the species are found in Ecuador and Peru.

The bark of several species of Cinchona has been the source for several centuries of the febrifuge chemical quinine, effective against malaria. In the Andes the bark has been widely harvested from wild Cinchona trees, which has reduced their populations. Several species and numerous hybrids have been cultivated in warm humid regions world wide, particularly India and southeastern Asia.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Charlotte Taylor, Charlotte Taylor |

| Source | No source database. |

Small to large shrubs and trees, unarmed, terrestrial, without raphides in the tissues. Leaves opposite, petiolate, with tertiary and quaternary venation not lineolate, on the lower surface often with pubescent and/or foveolate domatia in the axils of the secondary veins; stipules quickly deciduous, interpetiolar or sometimes shortly fused around the stem, triangular to ligulate, generally held erect and flatly pressed together in bud. Inflorescence terminal and in axils of the uppermost leaves, thyrisiform to paniculiform, multiflowered, pedunculate, with bracts develed to reduced. Flowers sessile to pedicellate, distylous, protandrous, medium to large, fragrant, apparently diurnal; hypanthium ellipsoid to turbinate; calyx limb truncate short, 5-lobed, without calycophylls; corolla salverform, white to pink, purple, or red, densely pubescent internally in throat and on lobes, lobes 5, triangular, valvate in bud; stamens 5, inserted in corolla tube, with anthers narrowly ellipsoid, dorsifixed near base, included to partially exserted; ovary 2-locular, with ovules numerous in each locule, imbricated and ascending on axile placentas; stigmas 2-lobed, included or exserted. Fruit capsular, cylindrical to ellipsoid or ovoid, septicidally dehiscent from the base and/or sometimes from the apex, chartaceous to woody; seeds flattened, small, irregularly elliptic to oblong, marginally winged and often erose.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Charlotte Taylor, Charlotte Taylor |

| Source | No source database. |

Native from mountains of northern Costa Rica to northeastern Venezuela and to Bolivia, from sea level to tree line but most of the species found in montane forests, above 1500 m elevation; and at least one species naturalized and weedy on some tropical islands.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Charlotte Taylor, Charlotte Taylor |

| Source | No source database. |

Cinchona has been confused with the very similar Rubiaceae genus Ladenbergia. In fact the separation of these was not clear for many years, but Andersson (1998) showed that species of Cinchona have white, pink, or purple flowers that open during the day and are hairy or fuzzy at the top of the tube and on the lobes, while Ladenbergia has bright white flowers that open during the night, and are not hairy or fuzzy at the top. Otherwise these two groups are difficult to separate. Previously they were sometimes separated by their fruits, which supposedly opened from the bottom in Cinchona vs. from the top in Ladenbergia, but Andersson showed that in fact this pattern of opening varies within both genera so this distinction does not actually work.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Charlotte Taylor, Charlotte Taylor |

| Source | No source database. |

The fruits are dry, rather woody capsules that open to release numerous small, papery, flattened seeds that are dispersed by the wind.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Charlotte Taylor, Charlotte Taylor |

| Source | No source database. |

The flowers are diurnal, and white, pink, or purple and generally very hairy or fuzzy in the mouth of the corolla tube. They are apparently pollinated mainly by butterflies and hummingbirds. The flowers are distylous: some plants have only flowers of the long-styled ("pin" form), with the stigma positioned at the top of the corolla tube and the anthers positioned below, inside the tube; other plants have short-styled flowers ("thrum" form) with the reciprocal or opposite arrangement, with the anthers positioned at the top of the corolla tube and the stigmas below, inside the tube. This reciprocal arrangement is believed to promote out-crossing and diminish pollination by the same flower form, by depositing pollen on different parts of the pollinator so that the pollen from the short-styled flowers is transferred to the stigmas of the long-styled flowers, and vice versa. In general the distylous type of flower also has incompatibility at the cellular level, so the pollen of long-styled flowers generally has a very low success rate in other long-styled flowers, and vice versa.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Charlotte Taylor, Charlotte Taylor |

| Source | No source database. |

Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) Stats

Specimen Records:351

Specimens with Sequences:132

Specimens with Barcodes:104

Species:23

Species With Barcodes:10

Public Records:11

Public Species:5

Public BINs:0

Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLDS) Stats

Public Records: 0

Specimens with Barcodes: 24

Species With Barcodes: 1

|

|

This article's introduction section may not adequately summarize its contents. To comply with Wikipedia's lead section guidelines, please consider modifying the lead to provide an accessible overview of the article's key points in such a way that it can stand on its own as a concise version of the article. (discuss). (March 2014) |

Cinchona, common name quina, is a genus of about 25 recognized species in the family Rubiaceae, native to the tropical Andes forests of western South America.[2] A few species are reportedly naturalized in Central America, Jamaica, French Polynesia, Sulawesi, Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, and São Tome & Principe off the coast of tropical Africa. A few species are used as medicinal plants, known as sources for quinine and other compounds.

The name of the genus is due to Linnaeus, who named the tree in 1742 after the Second Countess of Chinchón, the wife of a viceroy of Peru, who, in 1638 (according to accounts at the time, now disparaged) was introduced by native Quechua healers to the medicinal properties of cinchona bark. Stories of the medicinal properties of this bark, however, are perhaps noted in journals as far back as the 1560s–1570s.[citation needed]

It is the national tree of Ecuador[3] and Peru.[4]

Contents

Description[edit]

The Cinchona plants are large shrubs or small trees with evergreen foliage, growing 5–15 m (16–49 ft) in height. The leaves are opposite, rounded to lanceolate and 10–40 cm long.

The flowers are white, pink or red, produced in terminal panicles. The fruit is a small capsule containing numerous seeds.

Medicinal uses[edit]

The medicinal properties of the cinchona tree were originally discovered by the Quechua peoples of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, and long cultivated by them as a muscle relaxant to cease shivering due to low temperatures, also some symptoms of the Malaria. The Countess of Chinchon got the Malaria and the natives made her to immerse in a small pond beneath a tree; the water was bitter (due to the quinine contents); after few days the Countess was cured of the Malaria, when the scientific classification was mede the tree was named after the Chinchon Countess, Chinchona. Later the Jesuit Brother Agostino Salumbrino (1561–1642), an apothecary by training who lived in Loja(Ecuador) and Lima, observed the Quechua using the quinine-containing bark of the cinchona tree for that purpose. While its effect in treating malaria (and hence malaria-induced shivering) was entirely unrelated to its effect in controlling shivering from cold, it was nevertheless the correct medicine for malaria. The use of the “fever tree” bark was introduced into European medicine by Jesuit missionaries (Jesuit's bark). Jesuit Bernabé Cobo (1582–1657), who explored Mexico and Peru, is credited with taking cinchona bark to Europe. He brought the bark from Lima to Spain, and afterwards to Rome and other parts of Italy, in 1632. To maintain their monopoly on cinchona bark, Peru and surrounding countries began outlawing the export of cinchona seeds and saplings beginning in the early 19th century.

In the 19th century, the plant's seeds and cuttings were smuggled out for new cultivation at cinchona plantations in colonial regions of tropical Asia, notably by the British to the British Raj and Ceylon (present day India and Sri Lanka), and by the Dutch to Java in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia).[5]

As a medicinal herb, cinchona bark is also known as Jesuit's bark or Peruvian bark. The bark is stripped from the tree, dried, and powdered for medicinal uses. The bark is medicinally active, containing a variety of alkaloids including the antimalarial compound quinine and the antiarrhythmic quinidine. Although the use of the bark has been largely superseded by more effective modern medicines, cinchona is the only economically practical source of quinine, a drug that is still recommended for the treatment of Malaria.[6]

Ecology[edit]

Cinchona species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, including the engrailed, the commander, and members of the genus Endoclita, including E. damor, E. purpurescens and E. sericeus.

History[edit]

Peru offers a branch of cinchona to Science (from a 17th-century engraving): Cinchona, the source of Peruvian bark, is an early remedy against malaria.

- South America

| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

- Europe

The Italian botanist Pietro Castelli wrote a pamphlet noteworthy as being the first Italian publication to mention the cinchona. By the 1630s (or 1640s, depending on the reference), the bark was being exported to Europe. In the late 1640s, the method of use of the bark was noted in the Schedula Romana, and in 1677, the use of the bark was noted in the London Pharmacopoeia.

English King Charles II called upon Robert Talbor, who had become famous for his miraculous malaria cure.[7] Because at that time the bark was in religious controversy, Talbor gave the king the bitter bark decoction in great secrecy. The treatment gave the king complete relief from the malaria fever. In return, Talbor was offered membership of the prestigious Royal College of Physicians.

In 1679, Talbor was called by the King of France, Louis XIV, whose son was suffering from malaria fever. After a successful treatment, Talbor was rewarded by the king with 3,000 gold crowns and a lifetime pension for this prescription. Talbor, however, was asked to keep the entire episode secret.

After Talbor's death, the French king found this formula: seven grams of rose leaves, two ounces of lemon juice and a strong decoction of the cinchona bark served with wine. Wine was used because some alkaloids of the cinchona bark are not soluble in water, but are soluble in the ethanol in wine.

In 1738, Sur l'arbre du quinquina, a paper written by Charles Marie de La Condamine,lead member of the expedition, along with Pierre Godin and Louis Bouger that was sent to Ecuador to determine the length of a degree of the 1/4 of meridian arc in the neighbourhood of the equator, was published by the French Academy of Sciences. In it he identified three separate species.[8]

In 1743, on the basis of a specimen received from La Condamine, Linnaeus named the tree Chinchona citing La Condamine's paper. Establishing his binomial system In 1753, he further designated it as Cinchona officinalis[9][10]

- Homeopathy

The birth of homeopathy was based on cinchona bark testing. The founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, when translating William Cullen's Materia medica, noticed Cullen had written that Peruvian bark was known to cure intermittent fevers.[11] Hahnemann took daily a large, rather than homeopathic, dose of Peruvian bark. After two weeks, he said he felt malaria-like symptoms. This idea of "like cures like" was the starting point of his writings on homeopathy. Hahnemann's symptoms are believed to be the result of a hypersensitivity to cinchona bark on his part.[12]

Cultivation[edit]

The bark was very valuable to Europeans in expanding their access to and exploitation of resources in far-off colonies, and at home. Bark gathering was often environmentally destructive, destroying huge expanses of trees for their bark, with difficult conditions for low wages that did not allow the indigenous bark gatherers to settle debts even upon death.[13]

Further exploration of the Amazon Basin and the economy of trade in various species of the bark in the 18th century is captured by the extract from a book by Lardner Gibbon:

"...this bark was first gathered in quantities in 1849, though known for many years. The best quality is not quite equal to that of Yungas, but only second to it. There are four other classes of inferior bark, for some of which the bank pays fifteen dollars per quintal. The best, by law, is worth fifty-four dollars. The freight to Arica is seventeen dollars the mule load of three quintals. Six thousand quintals of bark have already been gathered from Yuracares. The bank was established in the year 1851. Mr. [Thaddäus] Haenke mentioned the existence of cinchona bark on his visit to Yuracares in 1796". (Source: Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon, by Lieut. Lardner Gibbon, USN. Vol.II, Ch.6, pp. 146-47.)

- Asia

In 1860, a British expedition to South America led by Clements Markham brought back smuggled cinchona seeds and plants, which were introduced in several areas of the British Raj in India and Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka, it was planted in the Hakgala Botanical Garden in January 1861.[14]James Taylor, the pioneer of tea planting in Sri Lanka, was one of the pioneers of cinchona cultivation.[15] By 1883, about 64,000 acres (260 km2) were in cultivation in Sri Lanka, with exports reaching a peak of 15 million pounds in 1886. It was also cultivated by British in 1862 in the hilly terrain of Darjeeling District of West Bengal, India. There is a factory and plantation named after Cinchona at Mungpoo, Darjeeling, West Bengal. The factory is called a Govt. Quinine Factory. Cultivation of Cinchona continues at places like Mungpoo, Munsong, Latpanchar, and Rongo under the supervision of the government of West Bengal's Directorate of Cinchona & Other Medicinal Plants.

- Mexico

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in Mexico by Matthew Fontaine Maury, a former confederate in the American Civil War. Postwar confederates were enticed there by Maury, now the "Imperial Commissioner of Immigration" for Emperor Maximillian of Mexico, and Archduke of Habsburg. All that survives of those two colonies are the flourishing groves of cinchonas established by Maury using seeds purchased from England. These seeds were the first to be introduced into Mexico.[16]

Chemistry[edit]

Cinchona alkaloids[edit]

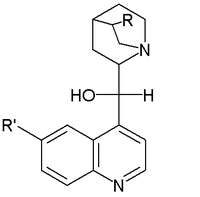

The bark of trees in this genus is the source of a variety of alkaloids, the most familiar of which is quinine, an antipyretic (antifever) agent especially useful in treating malaria. Cinchona alkaloids include:

- cinchonine and cinchonidine (stereoisomers with R = vinyl, R' = hydrogen)

- quinine and quinidine (stereoisomers with R = vinyl, R' = methoxy)

- dihydroquinidine and dihydroquinine (stereoisomers with R = ethyl, R' = methoxy)

They find use in organic chemistry as organocatalysts in asymmetric synthesis.

Other chemicals[edit]

Alongside the alkaloids, many cinchona barks contain cinchotannic acid, a particular tannin, which by oxidation rapidly yields a dark-coloured phlobaphene[17] called red cinchonic,[18] cinchono-fulvic acid or cinchona red.[19]

Species[edit]

There are at least 31 species acknowledged by botanists, and the list is growing, on account of the tendency of the various trees to hybridize. Resolution of other species is awaiting results of DNA studies. Several species formerly in the genus are now placed in Cascarilla.

Medicinal species[edit]

- Cinchona calisaya Wedd. (1848)

- Cinchona ledgeriana (Howard) Bern.Moens ex Trimen

- Cinchona officinalis L. (1753) - quinine bark

- Cinchona pubescens Vahl (1790) - quinine tree

- Cinchona succirubra

(Cinchona robusta represents various hybrids succirubra x officinalis)

Other species[edit]

|

See also[edit]

Note[edit]

- ^ According to legend, the first European ever to be cured from malaria fever was the countess of Chinchón, the wife of the Spanish Luis Jerónimo de Cabrera, 4th Count of Chinchón - the Viceroy of Peru. The namesake Chinchón is a small town in central Spain. In the Viceroyalty of Peru, the court physician was summoned and urged to save the countess from the waves of fever and chill threatening her life, but every effort failed to relieve her. At last, the physician administered some medicine he had obtained from the local Indians, who had been using it for similar syndromes. The countess survived the malarial attack and reportedly brought the cinchona bark back with her when she returned to Europe in the 1640s.

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Genus Cinchona". Taxonomy. UniProt. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ Motley, Cheryl. "Cinchona and its product--Quinine". Ethnobotanical leaflets. Southern Illinois University Herbarium. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Arcoiris Rerserve San Francisco Cloud Forest – Podocarpus National Park". Arcoiris Ecologic Foundation. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Deborah Kopka (12 Jan 2011). Central & South America. Milliken Pub. Co. p. 130. ISBN 978-1429122511. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Rice, Benjamin Lewis (1897). Mysore: A gazetteer compiled for Government Vol. 1. Westminster: A Constable. p. 892.

- ^ Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Second edition March 2010, World Health Organization, 2010. Available on-line at: WHO Document centre

- ^ See:

- Paul Reiter (2000) "From Shakespeare to Defoe: Malaria in England in the Little Ice Age," Emerging Infectious Diseases, 6 (1) : 1-11. Available on-line at: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- Robert Talbor (1672) Pyretologia: a Rational Account of the Cause and Cures of Agues.

- Robert Talbor (1682) The English Remedy: Talbor’s Wonderful Secret for Curing of Agues and Feavers.

- ^ Joseph P. Remington, Horatio C. Wood, ed. (1918). "Cinchona". The Dispensatory of the United States of America.

- ^ Linné, Carolus von. Genera Plantarum 2nd edition 1743. page 413

- ^ Linné, Carolus von. Species Plantarum. 1st edition. 1752. volume 1. page 172.[1]

- ^ William Cullen, Benjamin Smith Barton (1812). Professor Cullen's treatise of the materia medica. Edward Parker.

- ^ William E. Thomas. "Chapter 2: The basis of Homeopathy". Homeopathy; Historical Origins and the End.

- ^ Taussig, M. (1987). Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "Hakgala garden". Department of Agriculture, Government of Sri Lanka. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Fry, Carolyn (6 January 2007). "The Kew Gardens of Sri Lanka". Travel (London: Timesonline, UK). Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Sources: "Life of Maury" by Diane Corbin and "Scientist of the Sea" by Frances Leigh Williams.

- ^ Henry G. Greenish (1920). "Cinchona Bark (Cortex Cinchonae). Part 3". A Text Book Of Materia Medica, Being An Account Of The More Important Crude Drugs Of Vegetable And Animal Origin. J. & A. Churchill. ASIN B000J31E44.

- ^ Alfred Baring Garrod (2007). "Cinchonaceae. Part 2". Essentials Of Materia Medica And Therapeutics. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4326-8837-5.

- ^ "Quinine". Encyclopaedia Britannica (10 ed.). 1902.

References[edit]

- Reader's Digest, Strange Stories, Amazing Facts II; Title : "The Bark of Barks" -Reader's digest publication

- The Journals of Hipólito Ruiz: Spanish Botanist in Peru and Chile 1777–1788, translated by Richard Evans Schultes and María José Nemry von Thenen de Jaramillo-Arango, Timber Press, 1998

- Druilhe, P. et al. "Activity of a combination of three Cinchona bark alkaloids against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 32 (2): 25–254. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cinchona&oldid=651698479 |